Daniela Vacek from the Institute of Philosophy of the Slovak Academy of Sciences deals with the issues of artificial intelligence from an ethical point of view, but also with the philosophy and logic of responsibility. For her scientific activities so far, she received the SAS Award for 2023 in the category of young scientists. He considers freedom of thought and the opportunity to work on topics that interest only (a few) philosophers to be extremely important in his research.

You have also received an award for your results in the field of ethical issues of artificial intelligence. It’s a very topical topic, what are you actually researching?

Currently, I have three main topics in the ethics of artificial intelligence. The first is responsibility for the negative consequences of artificial intelligence. This question brought me to this area from the philosophy of responsibility and deontic logic (the logic of the commanded, forbidden or allowed). The main output of the research on this topic was an article with my colleague Matteo Pascucci on indirect liability: a solution to a problem of AI responsibility?, published in the journal Ethics and Information Technology, following our article on the theory of indirect responsibility, Making sense of vicarious responsibility: moral philosophy meets legal theory. published in the journal Erkenntnis). The second is control over artificial intelligence. One of the outputs of this research is my article on the new AI control problem (Two remarks on the new AI control problem, published in the journal AI and Ethics). The third topic is positive responsibility for the “good” results of artificial intelligence. This topic is still new to me, but I have already achieved results in it that I consider promising, although they have not yet been published.

One thing is scientific articles, another is application. Are there any conclusions or recommendations based on your articles?

Research on AI ethics often has practical conclusions and recommendations. Such is, for example, the research that we are doing with my colleague Matteo Pascucci on the control of intelligent technologies or research on the responsibility of artificial intelligence. In my opinion, it is positive if philosophers also produce such results that are interesting and relevant even for non-philosophers. At the same time, however, I consider the freedom of thought and the opportunity to work on topics that are of interest to only (a few) philosophers to be extremely important. Even if someone considered practical applicability to be the only value of research, given the interdisciplinary nature of most practically significant philosophical problems and their intertwining with other philosophical problems and questions, it would be harmful to “cut off” topics that are practically irrelevant at first glance. I am pleased that some of the results have practical use, but I do not consider them a necessity.

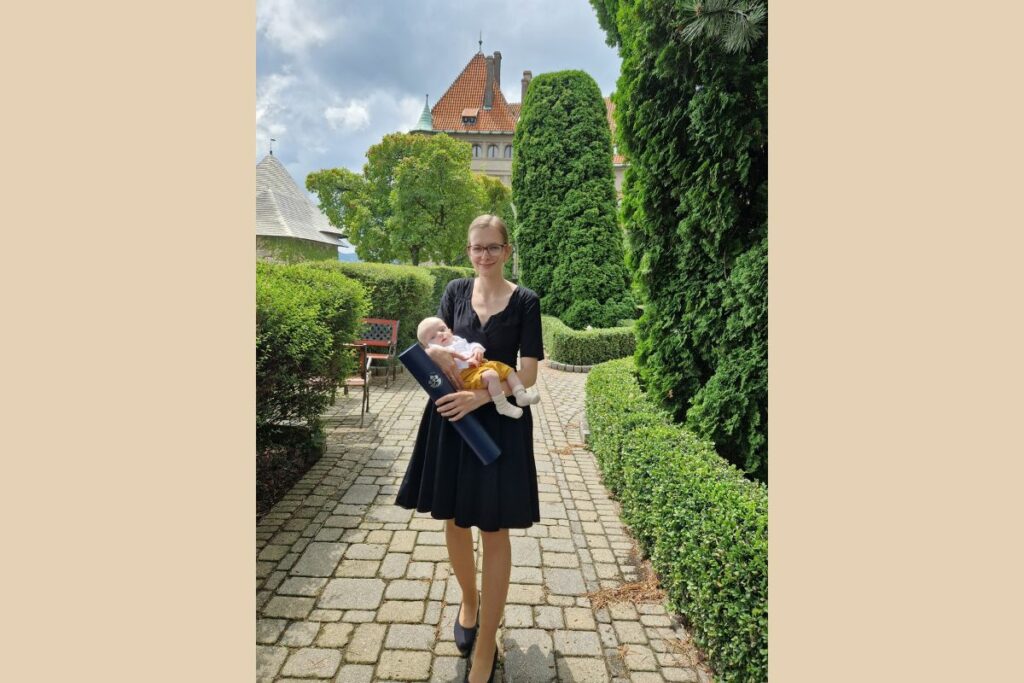

There are other activities associated with your research and publications, for which you have received awards. Do you manage it all – even with a baby?

Academic life certainly does not end with publications, although we are evaluated mostly for them. I am involved in many other activities: I lecture at conferences and workshops, review articles for prestigious journals or large international projects, organize academic events, work in committees such as the Executive Committee of the Slovak Philosophical Association at the Slovak Academy of Sciences or the Slovak Committee for Bioethics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences for UNESCO, write projects, lead discussion seminars, etc. It takes quite a lot of time to manage projects, starting with their administration and ending with their implementation. To a lesser extent, I am also involved in pedagogical activities. If possible, I also like to go on research trips, especially in the British Isles. At the moment, however, it is a little more complicated with mobility, because the most important project is now our baby. However, other activities persist, mainly thanks to my husband’s competence and the full support of my research in the workplace. I am very grateful for both.

You mention projects. You lead the (inter)national projects “Persons of Responsibility: Human, Animal, Artificial, Divine” and Philosophical and Methodological Challenges of Intelligent Technologies. What are they solving?

The international project “Persons of Responsibility: Human, Animal, Artificial, Divine” was acquired from the Ian Ramsey Centre at the University of Oxford and is funded by the John Templeton Foundation. This project addresses the question of actors and “patients” of responsibility (who is responsible and to whom). The project also considers less explored “persons of responsibility”, whether animal, artificial or divine. The national project Philosophical and Methodological Challenges of Intelligent Technologies (APVV-22-0323) deals with methodological, ethical and legal issues and problems of artificial intelligence. It figures moral and legal responsibility for AI and (potentially) gaps in this responsibility. In addition to philosophers, we also have lawyers involved in the project, which allows for the necessary interdisciplinarity. The co-investigator of the project is the Kempelen Institute of Intelligent Technologies, which I find very useful. This institute was acquired under the leadership of prof. In a short period of time, Bieliková has an excellent reputation and great international and national successes.

In your articles, we also encounter topics related to poetry or semantics and metaphysics of fictional characters. Outwardly, it seems far from artificial intelligence. Are there any common points in these researches? What does the semantics and metaphysics of fictional characters actually mean?

I’ll start from the end, philosophers like the mysteries of language and concepts. One of them is the question of how we can meaningfully talk about fiction (for example, about literary works or films), even though the objects and events described in them are often unreal, non-existent. For example, how can we attribute to Harry Potter the property of being a wizard when he doesn’t exist? As a rule, we assign properties only to objects that exist. There are many such mysteries in the field of aesthetics. To illustrate, another question is, for example, how and whether it is possible to translate poetry at all, when the poetic experience cannot be completely replicated in another language. Of course, this research in the field of analytical aesthetics is different from my research in the ethics of artificial intelligence. In my opinion, it is an advantage if a philosopher does not have a too narrow focus and at least somewhat resists the current trend, which leads to extremely specific and limited research focuses. Insight is also not a bad thing because many interesting questions (whether in the field of philosophy of artificial intelligence, philosophy of responsibility, or analytical aesthetics) are interdisciplinary. However, there are also research questions directly at the intersection of my focuses: such as, for example, the question of authorship and copyright or merits for works created by artificial intelligence or ethical issues of art vandalism.

Edited by: Andrea Nozdrovická

Photo: Martin Bystriansky and archive of D. V.